We all know who the world’s most famous footballers are. But it’s not just their names that we know, it’s also their shirt numbers. Think, for example, of:

Pele, Maradona, Zidane, Messi, Ronaldinho.

Cristiano Ronaldo, Beckham, Ribery, Cantona.

Maldini, Baresi, Cruyff, Beckenbauer, Ronaldo, Giggs, Butrageno, Zico, Socrates, Hurst, Puskas, Di Stefano,…

But are these numbers more than, well, just numbers?

What roles do shirt numbers really play? How are they chosen? And how are numbers allocated within a squad? What influence do shirt numbers have on individual players, or on the team? Is there such a thing as a shirt number factor?

These are the kind of questions we seek to address. And in researching the answers, one thing has already become clear: shirt numbers have a genuine impact on the game, although the nature of this impact on individuals and teams can vary considerably.

We can immediately observe two general concepts. First, shirt numbers provide structure, organisation and orientation. Second, when it comes to the choice of shirt number, superstitious beliefs are rarely far away.

A closer examination of both concepts reveals other impacts of shirt numbers on teams and players., and we’ll tackle these in future articles on how these numbers relate to, for example:

- Position (on the pitch and in the team)

- Role models (legendary shirt numbers)

- Self-confidence (the expected impact of a number)

- Fan expectations

- Confusing and surprising the opposition

Football historians are still debating when and where shirt numbers first appeared in competitive football. Was it England or Australia? 1911 or 1928? Or perhaps 1933?

All we need to know for our purposes is that players, the press, fans, managers and others have all been fascinated with shirt numbers ever since their invention.

Ghiggia

The first big, international tournament to feature shirt numbers was the 1950 World Cup in Brazil.

And the first shirt number to work its way into the world’s wider consciousness was the number 7, the shirt worn by Alcides Ghiggia. He scored the goal that gave Uruguay the title in the final against the host nation. There had never been so many people in a football stadium – and never been such a silence as the one that greeted the shot from the No.7 as it nestled in the back of the net for La Celeste’s second goal.

The number 7 can be considered a kind of “sacred” number. After all, in Christianity, there are 7 sacraments, 7 virtues and 7 deadly sins: the number plays a significant role in the bible.

Seven is also a common “favourite number” (especially in Uruguay in the 1950s?). Was it perhaps also the favourite number of Alcides Ghiggia?

Since he first set down a mark for the 7, a significant number of world-class footballers have played or still play with that number gracing their back. We can think of Garrincha, Dalglish, Cantona or Figo. And, of course, Cristiano Ronaldo (and Antoine Griezmann).

Garrincha is also the perfect example of how a shirt number can impact a player’s success.

Garrincha

The jury is still out on whether Garrincha is Brazil’s greatest ever player, but he is certainly their most popular.

He came to prominence playing for Botafogo in the 50s, with the number 7 on his shirt. But at his first World Cup (1958), it was the number 11 that accompanied his dribbling skills for the Selecao on their way to the title. Perhaps if he’d been able to wear his customary number (worn instead by the great Mario Zagalo), the 17 year-old Pele might not have been the one that stole the show that year.

Four years later in Chile, Garrincha was named best player of the tournament. Once Pele was injured, he carried the team on his own and led his country to a second successive title. His shirt number? Seven.

Garrincha’s best days were already behind him at the 1966 World Cup in England, with Orlando now wearing the number 7 in the team. After playing 49 (=7×7) matches for Brazil and never losing, Garrincha’s 50th and final appearance (against Hungary) brought his first defeat. The shirt number 16 did bring him some luck in England, though, since he scored against Bulgaria, but not enough luck to take Brazil beyond the first round. You can add the integers in 16 to get 7, but Garrincha’s greatest successes with both club and national team clearly came with the real number 7 on his back.

Until the 60s and 70s, only a very few players were able to pick their own shirt number. Instead, this number was allocated according to a players’ position within the team’s formation. The number 7 worn by Ghiggia and Garrincha was synonymous with the right winger.

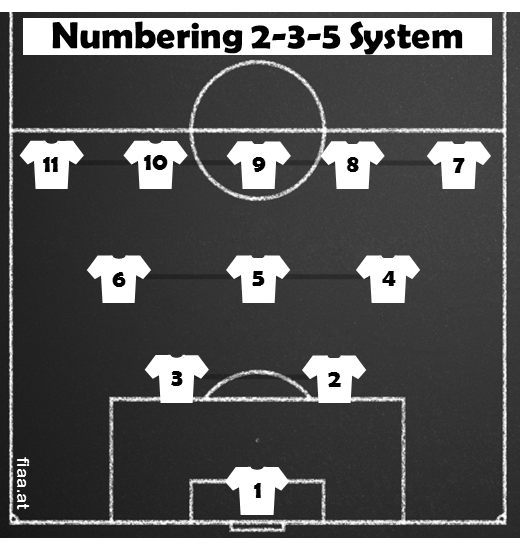

Position-based shirt numbers trace their origins to the English FA. At the end of the 1930s, they simply allocated numbers to positions on the pitch, without giving too much thought to possible tactical variations.

They assumed a 2-3-5 system (the pyramid), resulting in the following number-position combinations:

- Goalkeeper: 1

- Right back: 2

- Left back: 3

- Right half: 4

- Centre half: 5

- Left half: 6

- Right winger: 7

- Inside right: 8

- Centre forward: 9

- Inside left: 10

- Left winger: 11

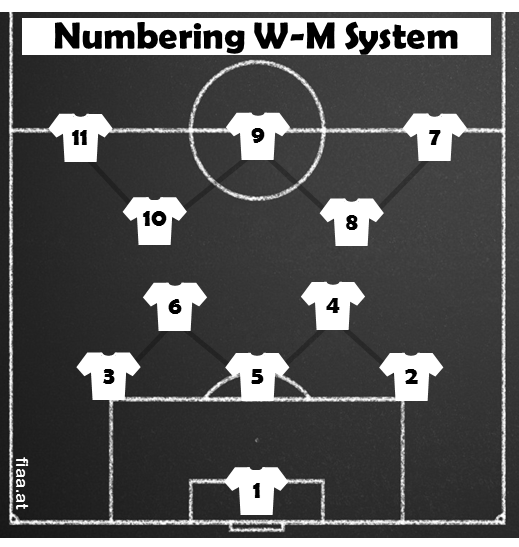

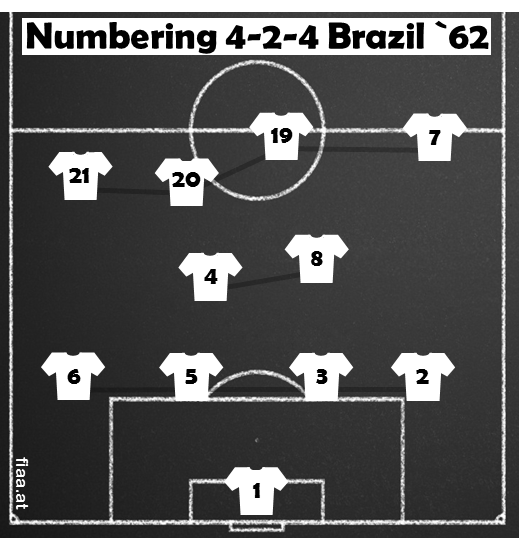

This numbering approach remained at the core of subsequent formations like the WM system, the classic 4-2-4 or the more modern 4-3-3 or 4-4-2. These new formations obviously brought changes in player positions and tactical approaches, but the numbering system stayed relatively constant and still has its echoes in today’s team setups.

Numbers as orientation

The arrangement of the opposition on the pitch is, of course, immensely important to a player facing them. In the past, you usually knew who your immediate opponents were, not least because of their shirt numbers. Everyone knew the numbers of the star player and the first eleven, but not those of reserves or new players. So there could be occasional surprises and confusion for players and reporters alike, especially at tournaments or when regular players were missing through injury or disciplinary bans.

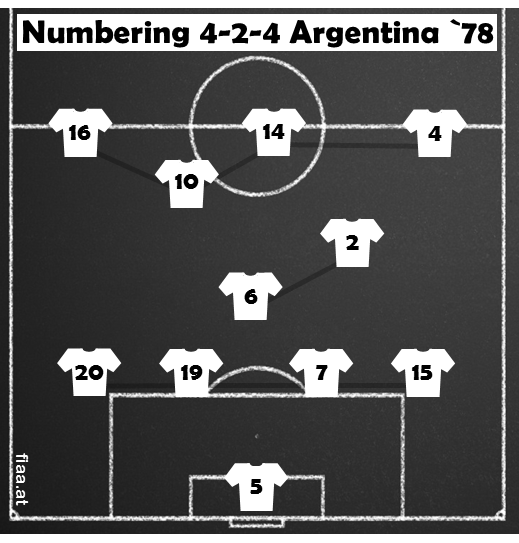

Holland took advantage of this concept at the finals of the 1974 World Cup by allocating squad numbers alphabetically: the only exception was the number 14, reserved for a certain Johann Cruyff. For example, the number 8 was goalkeeper Jongbloed, and the number 2 was the midfield dynamo Arie Haan. As a result, a cursory look at the shirt numbers revealed absolutely nothing about a player’s position.

The Argentinians followed the Dutch example when they hosted the 1978 World Cup. Goalkeeper Filiol was number 5, while Osvaldo Ardiles pulled the strings in midfield with the number 2 on his back. Mario Kempes, the eventual top scorer at the tournament, did have the number 10 – but only because he was genuinely tenth in the alphabetical list. Four years later and Ardiles – a midfielder remember – played in a shirt proudly displaying the number 1.

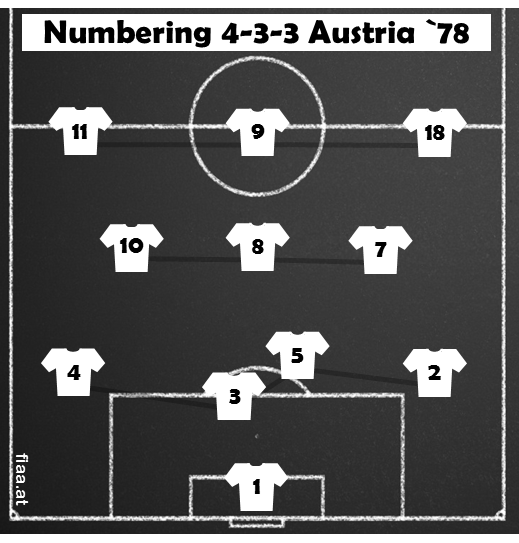

However, Holland and Argentina were the exceptions at major tournaments. The rest of the teams broadly kept to the FA’s numbering system first seen in the 1930s, even though the tactical formations had changed significantly. This is how the Austria team lined up, for example, for their first match – a 2-1 win over Spain using a typical 4-3-3 set up:

A similar set of numbers to those first found over 75 years ago can still be observed in 2016 in teams using 4-3-3, 3-5-2 or 4-1-3-2 systems.

With the passage of time, a couple of numbers became associated with a clear role for the relevant player – the number became the position.

Football experts speak, for example, of the number six, number eight, number ten or number nine. We know implicitly what role each of those players has within the team, even if those same experts may argue about the precise definitions of these roles.

We know the number six is a defensive midfielder charged with managing the build up of play. The number eight and number ten are midfield playmakers. The former is a hard-working box-to-box midfielder. The latter is a creative attacking midfielder, almost a striker, and often the team’s star player. The number nine is the traditional centre forward that you might already have found on pitches 100 years ago.

Two number sixes and a false nine

Managers and commentators have now begun to get more nuanced in their use of numbers-as-positions. So you have formations with two number sixes or a false nine. So you can find a manager at the start of the Premier League’s 2016/17 season saying something like this about the role of one of his players:

“Yes, his passing is amazing but my passing is also amazing without pressure. There are many players with a great pass but to be there and put the ball in the net is the most difficult thing to find. So, for me, he will be a nine or a 10 – a nine and a half maybe – but not a six and not even an eight.”

Jose Mourinho was, of course, talking about the Manchester United legend Wayne Rooney. It would be nigh on impossible to better communicate the past and future role of such a star player to an expert audience of football journalists without using more than three sentences.

Rooney now plays with the number 10. One or two of his colleagues are less pleased with their new squad number. Anthony Martial played the previous season as the number 9, but had to pass on his beloved number to a newcomer in the team, one who might indeed be considered a more traditional centre forward: Zlatan Ibrahimovic. He was obliged to do so, even though he had apparently trademarked “AM9”. So in 2016/2017, Martial plies his trade as the number 11, which we’ve seen is the traditional number for the left winger. Another striker and sensational young talent, Marcus Rashford, takes to the pitch with the number 19. At least the 18-year old still gets to have the number 9 on his back.

Time will tell how successful the three “number nines” are with the numbers 9, 11 and 19 on their respective shirts.

This example demonstrates a common “rule” in football. Older, more expensive or more successful players (or simply those who play regularly) tend to get priority when it comes to choosing shirt numbers. This natural hierarchy might be a device to ensure a quick end to disputes between players and avoid unnecessary conflict.

Thomas Müller, who wears the number 25 at Bayern Munich, has explained in detail why he wears the number 13 when playing for Germany. He had the choice of 4, 13 and 14, at which point he thought, “Hey, didn’t the old one wear 13?”, and that was that.

Germany and the number 13

By “the old one” he meant, of course, Gerd Müller. Müller G. began playing for his country after the 1966 World Cup, when the team already had its own legendary centre forward in the shape of Uwe Seeler. And Seeler wore (what else?) the number 9. After finishing as top scorer at the 1970 World Cup with 13 on his back, Müller decided to stick with his new lucky number – even though he still played with the number 9 for Bayern Munich throughout the 70s. And so it was that the German’s number 13 scored the winning goal in the 1974 World Cup final.

Thomas Müller, meanwhile, has also finished a world cup as the tournament’s top scorer and with the squad number 13 – this time in South Africa. Some might say it’s no wonder he is ambivalent about wearing 9 or 13. After all, he was born on 13.9.1989.

But we’re still not finished. The number 13 really is the definitive guarantee for goals in the German national team. No other number on a German shirt has scored so many goals in the finals of a world cup. Max Morlock, for example, scored during the “Miracle of Bern” and shot Germany to the 1954 title with his six goals across the tournament. You might recognise some other German number 13s who’ve scored at the world’s biggest football event: Uwe Reinders, Karlheinz Riedle, Rudi Völler and Michael Ballack!

Buffon

Choosing a shirt number can, however, also backfire, as goalkeeping legend Gianluigi Buffon discovered.

Bosman and the growing number of transfers in European leagues increased squad sizes and made it necessary to allocate numbers past 30 or even 40. In the 2000/2001 season at Parma, Buffon initially wore the number 88, not knowing that this is a Nazi symbol (H is the eighth letter of the alphabet, so 88 stands for HH or Heil Hitler). His cause wasn’t helped, either, by his ignorance of the fascist origins of the “Boia chi molla” (roughly translated as “to hell with those who give up”) phrase he’d proudly displayed on his vest the season before. His explanation for his choice of 88 contained a few surprises:

“I have chosen 88 because it reminds me of four balls and in Italy we all know what it means to have balls: strength and determination” – “And this season I will have to have balls to get back my place in the Italy team.”

He continued: “At first I didn’t choose 88,” he explained. “I wanted 00 but the league told me that was impossible. I also considered 01 but that was not considered a proper number. I liked 01 because it was the number on the General Lee car in the TV series the Dukes of Hazzard.”

He changed his number, of course, and subsequently played for Parma with the number 77. The choice caused him no further trouble, even if 77 means “ladies legs”, “the devil” or “horns” in Italian bingo (“le cambe delle donne” / “I diavoletti” / “le corna”). He switched to Juventus at the end of the season, where he took a more conservative route by playing with the number 1.

Coincidence? Destiny? 21?

Andrea Pirlo – another Italian great and world cup winner (2006) – has worn the number 21 for both club and country for years. He explained why in his autobiography, as quoted by 90min.com:

“My dad was born on the 21st. It’s also the day I got married and made my debut in Serie A…it became my shirt number early on and I’ve never let it go.”

You can also find the number 21 on the shirt of Marc Janko, currently the top goalscorer in Austria’s national team. At the time of writing, he’d scored 26 goals in 56 international appearances, and 17 goals in 22 games for his club (FC Basel). He has also topped the goalscoring charts in both Austria and Australia. His thoughts on his choice of number for both club and country are perhaps the most amazing ever uttered by a footballer on this theme. In an interview with Die Presse, he said (our rough translation):

“The number 21 has appeared positively throughout my life. The integers in my year of birth add up to 21, as do the integers in the code for my first ATM card. The code for the Bluetooth connection in the car is 2121. I signed my first contract as a professional with Twente Enschede on June 21st and that club was founded in 1965 – those integers add up to 21. We first felt my daughter moving in the womb on December 21st in the 21st week of pregnancy. As a rationalist, I am well aware that we look for such things and quickly forget other numbers and outcomes. And if people want to laugh about it, well, I can live with that.”

As the Janko quote proves, a footballer’s choice of a particular number can be a deliberate one, perhaps associated with particular personal motivations. Or it might just be random. However, once a number attains some kind of symbolic status, becomes a lucky charm, then that player will be reluctant to switch to another one.

Whatever reasons lie behind a choice, there are two overriding aspects to consider.

- A player must simply feel comfortable with the number on his back. They may not have a particular preference, but they will certainly not want to take to the pitch a second time with a number they actively dislike.

- Even more importantly, what impact does the player think the number has? Is it a number that brings me luck? That induces self-confidence? That somehow gives me additional abilities? That lets me handle defeats better?

Such questions are growing in importance for top professionals in team sports. Which is one more reason why choosing the right number has become another factor in determining the success and performance of individuals in modern football.

In future articles on the topic of the shirt number factor, we’ll explore, for example, the numbers behind the famous players, and the players behind famous numbers. In the meantime, when you next watch a game, pay attention to the shirt numbers both on and off the pitch and you may well see how they are impacting the game in front of you.